The Eastern Equine Encephalitis virus is a severe alphavirus that was first detected in humans during the historic 1938 outbreak in Massachusetts. Instances of viral transmission of EEE to humans and horses occur regularly in North America, where it is considered endemic. Since its first detection in Massachusetts in 1938, there have been about 119 documented human cases of the disease. Historically, EEE has been more prevalent in Bristol, Plymouth, and Norfolk Counties. However, in recent years, EEE has also had a significant impact on additional communities located in Central and Western Massachusetts.

Symptoms and Risk Factors

The transmission of EEE to humans is very rare; however, approximately 40% of cases have resulted in death from 2003 to 2022. Children and the elderly are at a higher risk of dying from the disease. The onset of symptoms for EEE ranges from 4 to 10 days. The symptoms for the neuroinvasive disease include fever, headache, seizures, changes in behavior, vomiting, diarrhea, and coma. Those who recover from neuroinvasive disease often experience long-term cognitive impairments that require life-long medical interventions. Febrile illness is a less severe form of the disease and typically includes the following symptoms: fever, muscle and joint pain, and chills—similar to the flu. Recovery from febrile illness tends to occur within 1 to 2 weeks of the onset of symptoms.

EEE Transmission Cycle

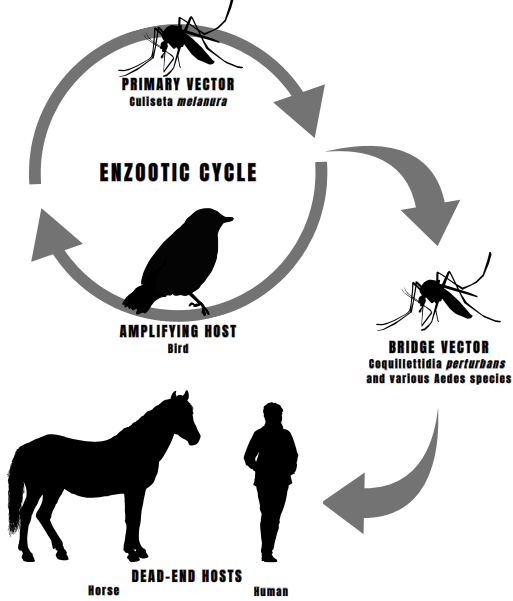

The EEE transmission cycle involves mosquitoes, birds, and mammals, including humans and horses. The cycle begins when Culiseta melanura mosquitoes, which breed in freshwater swamps, feed on infected birds. Birds are the primary reservoirs of the virus, harboring it in their bloodstream without showing symptoms.

After feeding on an infected bird, the virus replicates within the mosquito. The mosquito can then transmit the virus to other birds, continuing the cycle. Other mosquito species, such as Aedes, Coquillettidia, and Culex, which are bridge vectors, feed on both birds and mammals, transmitting the virus from birds to humans and horses.

Like WNV, humans and horses are considered dead-end hosts because they do not develop high enough levels of the virus in their bloodstream to infect other mosquitoes, thus not contributing to the spread of the virus.